Is our national rite of passage the right cost?

April 6, 2021

When it comes to higher education in America, there’s so many criticisms to lodge, it’s hard to know where to start. The root of our problems, like most things, is money.

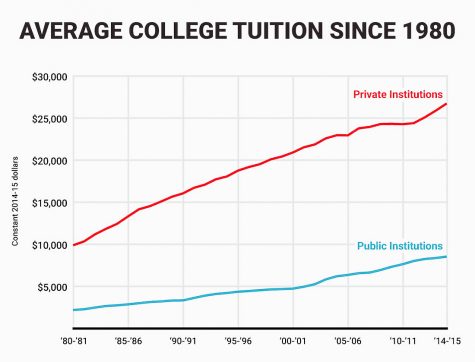

“The sticker price of American college increased nearly 400 percent in the last 30 years, while median household income growth was relatively flat,” Derek Thompson, journalist at The Atlantic, said.

This cost has culminated in over $1 trillion in student loan debt, a hot-button issue. While it’s easy to dismiss these intangible debates, student debt isn’t just a concern for families and young people; it’s a threat to our economy and a burden to student’s entire lives.

But before we wonder what we can do, we must ask: how did we get here?

The short answer refers to the double-edged sword of college enrollment trends.

The long answer starts in 1944, when President Roosevelt signed the GI bill, dedicated to supporting the soldiers after the second world war. It guaranteed that both former and current military members could receive a tuition-free higher education, including vocational school as well as college. 7.8 million military service members gained a degree or vocational trading thanks to this bill, and forever changed society along with it. It’s worth noting that many black veterans were excluded from these benefits, reinforcing the idea of higher education as an opportunity only for the privileged. An estimated 40 percent of those veterans would not have been able to attend college otherwise. This bill rapidly expanded the middle class, bridging the divide between the ultra rich and destitute.

According to procon.org, a bipartisan organization dedicated to informing citizens on political issues, GI Bill recipients generated an extra $35.6 billion over 35 years and an extra $12.8 billion in tax revenue, resulting in a return of $6.90 for every dollar spent. The rationale was that with the right skills and the personal growth that colleges often facilitate, graduates were more likely to vote, volunteer, donate, and would certainly be able to gain more financially profitable and powerful jobs.

Statistically, they were right, at least to some degree. The bill made sure that brave young men were not left helpless in a world they were unaccustomed to, and in the meanwhile, boosted the economy. The 1944 GI bill paid for the education of 22,000 dentists, 67,000 doctors, 91,000 scientists, 238,000 teachers, 240,000 accountants, 450,000 engineers, three Supreme Court Justices (Rehnquist, Stevens and White), three presidents (Nixon, Ford and H.W. Bush), many congressmen, at least one Secretary of State, 14 Nobel Prize winners, at least 24 Pulitzer Prize winners, many entertainers (including Johnny Cash, Paul Newman and Clint Eastwood) and many more. Higher education had never been more widespread and affordable to a new class of people.

Sounds great, right?

Not exactly.

While in many ways the bill was a testament to the benefits of college, it was also the start of the enrollment trend that reduces the very value of it, more than 75 years later.

Although students still generally state higher income and a better career as their reasoning for attending college, higher education has undergone a cultural shift. Yes, in the past, young people experiencing their “firsts” during college was fairly probable. But more than ever before does higher education symbolize a period of personal growth, with ethereal checkpoints such as “finding yourself” and becoming more cultured. In fact, in 2019-2020, 80 percent of Americans considered college to be part of the American dream, according to a survey on Isopos.

But beyond the statistics, it’s no secret that society regards college as a right of passage, a nearly obligatory transition period between childhood and adulthood, especially for predominantly white, upper middle class suburbs like Scotch Plains-Fanwood.

“If you have the money to spend 100k on college for the ‘experience’ like it’s nothing then by all means do so,” senior Sean Merkle said. “However, the world is full of meaningful experiences, so if you aren’t going for the sake of learning or to expand your career opportunities, then I think it is a poor financial decision.”

Student Loan Hero, an organization dedicated to helping students with their debt, indicated that although wages have grown 67 percent since 1970, the cost of tuition has outpaced this rate. On the other hand, the US has witnessed a steady increase of professions and employers that demand a bachelor’s degree: according to CNBC, in 2020, 65 percent of jobs will require a degree to even be considered.

It’s the ultimate catch 22.

Even though degrees are seemingly more necessary than ever, thanks to new requirements and implicit social pressures, rising costs paired with increased enrollment reduce its value.

This contributes to underemployment. An estimated 22 million US workers are working part-time or at a job that does not fully utilize their experience, training and education. The effects have remarkably similar effects as unemployment. Essentially, underemployment is a fancy term for a graduate with a bachelor degree working at McDonald’s (as their primary source of income).

“The value of a degree has become something of a self-fulfilling prophecy: it’s become worth so much because people assume it should be,” Daniel Indiviglio of The Atlantic said.

The intangibility of perception makes it all the more dangerous.

COVID, and the consequential economic recession, only compounds the entangled mess of higher education. With deferrals and declining financial states, the enrollment trend has declined. Colleges lost about 400,00 students in fall 2020. The increase in deferrals presented new problems. While this decline in demand may be beneficial in decreasing the value of a college degree, higher education is generally losing money, which may raise prices in the long run even more.

“It’s crucial to look at the numbers and examine your personal financial decision,” guidance counselor Luke Kostu said. “What can you afford? Is your major going to earn you enough money to pay back your investment?”

Ultimately, the price of college is a burden that no one should have to pay, much less America’s students, brimming with youth and potential. Let’s give them a fighting chance to enter the world, which seems to be getting harder to navigate with each passing day.