Exclusive interview with The Fanscotian: Trevor Pour discusses COVID-19’s cultural impact, the future and more

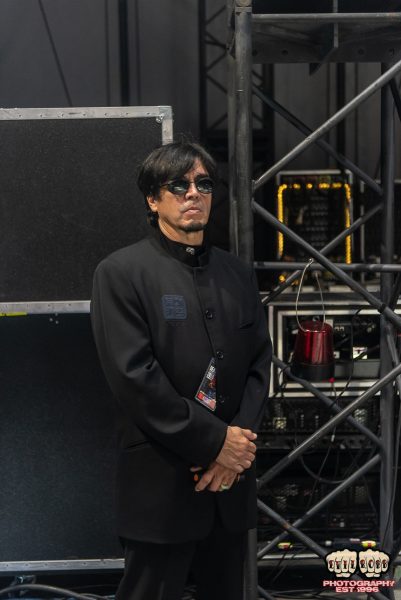

Photo courtesy of Ajay Suresh/Creative Commons/via Wikipedia

Pour works at Mt. Sinai Hospital in Manhattan, New York, New York. Pour, along with many of his colleagues, received the COVID-19 vaccine in late December 2020.

February 18, 2021

Trevor Pour was one of the first in line to get vaccinated in the state of New York.

His coworkers at Mount Sinai Hospital began to register for their injections; there was a sense of relief in the air of the hospital halls. Pour, though, begrudgingly took the vaccine knowing that he’s a healthy 37-year-old and the patient he attended to last night in bad shape probably needs it more than him.

“It was an interesting feeling,” Pour said. “I kind of felt a little bit guilty getting it because I felt like that dose should go to somebody who’s like 90 or has chronic medical problems or something, but I trusted the system. I took it. I’m happy. It’s one step forward.”

As the warm forecasts last spring became more common, Pour and his colleagues felt that things were finally looking up for the time being. He hadn’t seen a COVID-19 patient walk down the halls of Mount Sinai Hospital in weeks. And he more confidently commuted from his Brooklyn apartment into the depths of Manhattan (with his mask on, of course).

Before long, warm forecasts were traded for leafless trees, and like everything, optimism amongst the public abruptly faded. Pour’s sense of security in the fates of his patients washed away as the anxiety crept back in en route to the COVID-19 frontlines.

If people want to get together and hang out as a family with the recognition that maybe grandpa’s gonna get COVID and die, fine. That’s up to them,” Pour said. “But I think when you’re out in public, and you’re doing things like, you know, not wearing a mask at an indoor area or something like that, that’s just like gratuitous harm to someone else.

— Trevor Pour

“And now it’s coming back, you know, I saw one pretty severe COVID patient last night,” Pour said. “So, the anxiety… to a small degree is coming back because we’re just seeing patients again and it had been a long time that we weren’t seeing really sick people coming in.”

As the pandemic’s one year anniversary is upon us, Pour remains frustrated by the lack of empathy and care people are showing towards the pandemic. He cannot understand why people refuse to believe in the science behind coronavirus research.

“I’m glad I got [the vaccine]; I obviously believe the science,” Pour said. “I actually am gonna take that word back; I don’t believe the science, I understand the science, it’s not a belief, it’s like it makes sense.”

When dealing with COVID-19 patients, people who know the coronavirus far more personally than anybody else, Pour humanizes his conversations and does his best to be honest about the implications of this virus.

“If I think that somebody is doing something that’s harmful, if I think they’re taking a medication that I know doesn’t work and will cause harm, or if they want to leave the hospital and I don’t think they’re going to do well if they go home, in those situations I usually… I’m just very honest with them,” Pour said.

“I say, ‘you know, I think there’s a chance that you might die at home if you go home. And I need you to understand that that’s something I’m saying and you need to be okay with that and you need to say back to me, ‘I’m okay dying at home,’ before I let you go.’ Doesn’t happen a lot, a lot of times I’ll often kind of say, like ‘if you were my parent, this is what I would recommend,’ or ‘this is what I would want for you,’ or ‘if I was in your situation, this is what I would do.’”

As the pandemic raged on, Pour began to feel more comfortable with outdoor activities, permitting he was masked. Mask-wearing became such a habit for him that he forgets to take it off while driving. He felt “naked” on one occasion when he left home before putting his mask over his face.

“If people want to get together and hang out as a family with the recognition that maybe grandpa’s gonna get COVID and die, fine. That’s up to them,” Pour said. “But I think when you’re out in public, and you’re doing things like, you know, not wearing a mask at an indoor area or something like that, that’s just like gratuitous harm to someone else. I don’t think there’s any good excuses for that. As far as I know, there is no medical reason why someone can’t wear a mask, except maybe anxiety, that’s a legitimate medical reason potentially, but there’s no lung problems that are impeded by wearing a mask so a lot of that stuff is kind of made up.”

I’m glad I got [the vaccine]; I obviously believe the science. I actually am gonna take that word back; I don’t believe the science, I understand the science, it’s not a belief, it’s like it makes sense.

— Trevor Pour

Pour doesn’t see people as the greatest barrier to providing quality healthcare; he feels that the wildfire of misinformation that spreads across the nation is responsible for that. The media circus and politicizing of the pandemic – among other things – has undoubtedly taken a toll on Pour.

Earlier in the pandemic, he remembers a study coming out that stated roughly 90 percent of people who were intubated died.

“There was a lot of press back in the spring that if you got intubated, you’re probably going to die,” Pour said. “And a lot of people still believe that. It was based on some pretty bad evidence. And unfortunately, a lot of people still believe that you shouldn’t get intubated because if you get intubated it’s a death sentence.”

“The data and the research have shown us that’s not true. If your oxygen levels are low, and we can’t get them up any other way, it’s really the best way to give you a better chance of surviving. There was a study that was done that showed that like 90 something percent of people that got intubated died. And the study design was not great. But, it did still show that result so they saw that result and they said ‘oh my gosh, this is like, you know, the sky is falling,’ and that kind of news sells, so it got published and everyone read it.”

Post-pandemic, will there be a life sans handshakes and will mask-wearing be a part of the culture?

“I think there’s a chance that we might end up getting annual COVID shots, the same way we get flu shots now,” Pour said. “They might just be part of our lives from now on. I think that for the most part, our lives are gonna be back to normal by the end of this year. But there’s gonna be some long-standing changes, like people are going to be a little bit more thoughtful about, you know, touching other people’s hands without washing theirs first. I think eating indoors is going to be a little bit weird at first but I think we’ll get back to that. The best way to think about it is [to] look at New Zealand, which basically eradicated the virus…. They’re eating indoors, they’re having concerts, they’re back to normal and they feel fine about it. But we’re just not close to that yet. We’re going in the wrong direction. Still.”