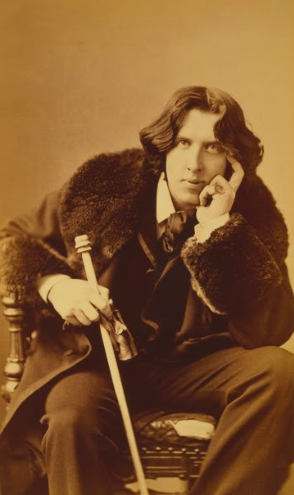

The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

December 11, 2020

Oscar Wilde has long been hailed as a literary genius, an author of several classic plays. The Picture of Dorian Gray is his only novel, detailing the slow corruption of the titular character, Dorian Gray.

Dorian is described as a startlingly beautiful young man, someone who captures the eye of whomever he meets, including the artist Basil Hallward. Basil, immediately taken with Dorian’s innocence and beauty, asks him to sit for a painting. It is at this point that Basil’s friend, the immoral Lord Henry, begins to regale Dorian with his personal philosophy, which Basil believes to be a bad influence. The portrait is the best Basil has ever done, yet Dorian is saddened by it due to the influencing of Lord Henry. He cries, “How sad it is! I shall grow old, and horrible, and dreadful. But this picture will always remain young… If it were I who was to be always young, and the picture was to grow old!” From there on, Dorian begins to be taken in by Lord Henry’s views, descending into infamy and corruption.

The Picture of Dorian Gray is a comment on aestheticism, of which Oscar Wilde was a proponent. In the preface of his novel, Wilde remarks that, “there is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book” and that “all art is quite useless.” To understand some of the major themes in the book, there is a little bit of research to be done about the art world at that time. When this book was published there was a growing concern about how art should be appreciated, and one of the ways to think about art was through the lens of aestheticism. Aestheticism’s philosophy is that art is not supposed to have a purpose beyond being admired or even disliked. This is evident throughout the novel and especially through the voice of Lord Henry’s character, who says, “And beauty is a form of genius—is higher, indeed than genius, as it needs no explanation.”

The crafting of Lord Henry’s character is central to the purpose of Wilde’s writing. Lord Henry is essentially Wilde’s own voice within the story, embodying the ideals of aestheticism. He is the negative influence on Dorian, prompting his change in character through long, flowery speeches on his twisted philosophy and the gift of a book detailing the debauched life of a Frenchman.

Dorian’s change in outlook is apparent to those around him, but the most solid symbol the audience is given is the portrait painted by Basil Hallward. This portrait grants Dorian’s wish — though Dorian remains young and beautiful, the portrait shows his age and cruelty. It serves as a reflection of Dorian’s own soul, making it ever clearer to the audience how he has changed.

Wilde paints a vivid portrayal of Dorian’s demise, often using allusions to other classic literary works or phrases in different languages (notably French, Latin, and Greek). The dark tale is punctuated by glowing descriptions of beautiful imagery, neatly juxtaposing the ever growing immorality within Dorian’s heart.

There is a reason why The Picture of Dorian Gray is hailed as a literary masterpiece; everything from the crafting of Wilde’s syntax to the way some characters seem almost playful while others feel heavy draws the reader in. Though parts of the novel can be somewhat dense (more than three pages of description on Dorian’s debauchery), it is a page turner without question.

I would recommend this novel to those interested in classic literature and dark storytelling. It requires quite a bit of time to read through, so for casual readers and those with busy schedules, I would suggest something lighter. Here is a sample passage from the book:

“The studio was filled with the rich odour of roses, and when the light summer wind stirred amidst the trees of the garden, there came through the open door the heavy scent of lilac, or the more delicate perfume of the pink-flowering thorn.

From the corner of the divan of Persian saddle-bags on which he was lying, smoking, as was his custom, innumerable cigarettes, Lord Henry Wotton could just catch the gleam of the honey-sweet and honey-coloured blossoms of a laburnum, whose tremulous branches seemed hardly able to bear the burden of a beauty so flamelike as theirs; and now and then the fantastic shadows of birds in flight flitted across the long tussore-silk curtains that were stretched in front of the huge window, producing a kind of momentary Japanese effect, and making him think of those pallid, jade-faced painters of Tokyo who, through the medium of an art that is necessarily immobile, seek to convey the sense of swiftness and motion. The sullen murmur of bees shouldering their way through the long unmown grass, or circling with monotonous insistence round the dusty gilt horns of the straggling woodbine, seemed to make the stillness more oppressive. The dim roar of London was like the bourdon note of a distant organ.”